Democratic Principles in Australians Government Order Instructions: To what extent does Australia’s system of government reflect basic democratic principles, and to what extent not.

Answer the above question giving specific examples and insight into the issue.

Also include NEWS ARTICLES, YOUTUBE CLIPS and ACADEMIC SOURCES to strengthen the argument.

1500 word essay.

Democratic Principles in Australians Government Sample Answer

To what extent does Australia’s system of government reflect basic democratic principles, and to what extent not.

Australia has enjoyed very stable democratic institutions for a long time and at Federation took pride in being a very young nation but an old democracy. Australia is quite a different type of country than it was in 1901 and “Brutishness” no longer provides the other aspect of its identity. Since 1989, there have been various attempts to articulate a civic identity as an alternative to an ethnically based national identity. Sets of core values or basic principles associated with Australian democracy have been identified, and, recently, the Australian Citizenship Council has urged acts of public commitment to these shared democratic principles, including acceptance of democratic diversity and recognition of the status of Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal peoples as well as the strengthening of the parliamentary democracy (Levey, n.d.).

Despite such affirmations, many believe that trust in representative institutions has eroded rather than strengthened in recent times. Surveys find a gap between the policy preferences of voters and those of their elected officials (Galligan & Roberts, 2004). This gap can be particularly large on issues such as immigration. There has been resentment in some parts of the country that immigrants no longer need to come from Britain or at least to assimilate to full citizens. This resentment fuelled support for populist politicians who claimed to be a voice for the people rather than for the political elite. Moreover, a civic identity based on sound democratic principles is not in itself sufficient for ensuring national cohesion, particularly in multi-ethnic or multinational states. There needs to be some emotional identification with the history of the nation. In the Australian context, knowledge of and pride in, the democratic struggles and accomplishments might promote such identity without the need for any racial pride (Birch, 2001). There exists evidence from the International Social Survey Program of 1996 that pride in Australia’s democracy is very high by international standards, exceeded only by New Zealand, Norway, Canada and Britain. There is distrust of politicians, and the country does not rank so highly on this indicator, but there is still less distrust than in most countries. While pride in democracy still plays such a role in Australian national identity, there can be some optimism for the future, despite the cultural and economic insecurities of the present (Cook, 2004).

In any democratic political system, the executive is required to accountable i.e. should be held responsible for its administrative practices and decisions. One of the most significant principles of democracy in Australia is that voters/people have a choice of government (Foley, 1996). To keep with this expectation’s spirit, the opposition is recognized as being the next largest party in Australia. This implies that the party forming the opposition is thought of a party that lost the last election based on the numbers in the State Legislative Assembly or the House of Representatives. The Australian government has embraced democracy allowing opposition that plays a vital role of keeping the government accountable and honest (Lindell, 1994). Traditionally, the opposition forms a shadow cabinet that scrutinizes government officials and proposes alternative ideas and amendments to government legislation. In this context, the shadow opposition cabinet plays a significant role in criticizing the agenda of the government as well as pointing out any shortcomings of the top leadership i.e. the ministerial team or the Prime Minister (Smith, 2012).

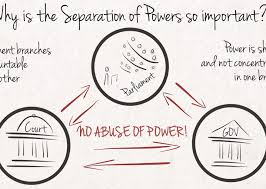

Fundamental democratic principles are reflected by the Australian government’s separation of powers in order to define distinct and discrete functions and roles as well as avoid a monopoly of authority (Galligan, 1995). The functional basis of the separation of powers has enabled expertise and professionalism required in exercising various governmental powers, especially judicial power, has been perceived in a way which was impossible under the earlier notions of ‘balanced government’ which had viewed the various ‘estates’ held in balance merely as centers of power. There was, for example, no inherent reason why the nobles should sit in Parliament, rather than, say, the lower clergy or the landless peasantry, except that one group held social or economic power and the others did not. But the separation of powers doctrine highlighted the need for democratic input into legislation and, in the case of the judicially, for independence and professional expertise, which received early recognition (Keating, 2004).

Separation of power has made the way the Australian government system works differently. In the First place, it has prevented the courts from being given powers that are non-judicial (Hart, 2008). Federal courts could not be asked to negotiate or arbitrate industrial disputes, for example because arbitration is an executive power. Federal courts could not be called upon to agree to continue keeping dangerous offenders in gaol after they have served their sentence, as some state courts have been. That power is not judicial either. Separation of power has also prevented other bodies using judicial power. Over several years, this has had its primary impact on organizations that are set up to deals with disputes of various kinds but which do not meet the definition of the courts. An example of these was the Interstate Commission established under section 101 of the Constitution (Keating, 2004). This commission was supposed to have powers of adjudication and administration over disputes about how the parts of the constitution dealing with economic matters worked. In 1915, the high court said that whatever those words meant, the commission would not use judicial power because its members were appointed only for seven years and so it was not a court. This made the commission less necessary, and it no longer exists. Separation of judicial power means that parliament cannot use judicial power either. This is essential especially for the protection of individuals under the Australian Constitution. For example, Parliament cannot pass a law to say that a particular person has committed a crime and to punish them for it because this is judicial power. On the other hand, the separation of judicial power has limited the instructions that Parliament can give the courts about how to do their work. The separation of powers has been necessary for preventing tyranny and preservation and maintenance of people’s liberty. This is because a separation of powers is the best means for institutionalising the rule of law the idea that an objective set of publicly known as rules are applied transparently and equally to all people (Peabody, 2011).

To some extent, the precise role of the courts in the country is hotly contested. A maxim of democratic governance is that, in accordance with the doctrine of the separation of powers, a separate and independent branch of government is granted judicial powers. The other two branches of government- the legislature and the executive- are compressed to debate enact and implement laws and policy. The judicially, through the court system, interprets and applies those laws independently of government. The judiciary, in, turn, is required to restrict its role to interpretation and enforcement of relevant laws, rather than seeking to usurp the roles of the executive and legislature (Keating, 2004). In principle, this all sounds logical and straightforward. In practice, however, it is anything but, Australian courts often find themselves at the centre of political storms (Youtube). Parliamentarians and public commentators have publicly derided their decisions, and members of the public have called for parliaments to step in and specify to the courts the length and type of sentences that ought to be imposed for certain offences, thereby overriding the discretion of judges. This implies that the activities of the courts are often as hotly debated as the activities of other government branches (Keating, 2004).

Australian government has adopted a strange position on the protection of human rights and the human rights bodies and parliament have been left to defend people’s liberty. This is against the strict separation of powers (Youtube). The government criticizes the efforts of the human rights bodies and fails to recognize that parliament has a task of ensuring that the laws in the country comply with human rights standards. Therefore, the government seems not to support the basic democratic principles and enhances the disappearance of the mechanisms that ensures compliance of the federal laws with human rights norms (Davis, 2015).

In theoretical terms, a major concern has been whether federalism is compatible with democracy- a concern on which some theorists disagree. Much of theoretical debate about the advantages and disadvantages of federal systems stems from the varying weights given to democratic and liberal values (Kincaid, 2005). Considering the principle of the popular control of the Australian government, one of the advertised virtues of federalism has been the checks and balances it places on the potential for democracy to lead to ‘big government.’ Supporters of federalism emphasize the way in which divided sovereignty disperses the power of central government by creating competing centres of power. Some believe this competition curbs corruption by providing multiple levels at which allegations can be aired under parliamentary privilege (Dahl, 2003). The limiting of each jurisdiction’s power to particular policy areas, and to geographical regions in the case of sub-national governments, is also seen as restricting the growth of government. The tortuous and legalistic decision-making process associated with federalism have been favourably interpreted as slowing governments down and hence ensuring due process or at least a break from arbitrary action (Harris, 2002).

The founding fathers of federalism were particularly concerned about the danger to property rights that might be posed by popular movements in a new democracy and this came to be seen as a more general threat to individual or minority rights (Patapan, 2000). Federalism was said to be a defence against the overbearing majorities that democracy might produce. By dividing the power to govern, federalism could be a means of taming democracy in Australia and creating a defence against the people who would legislate ‘happiness schemes’ (Hudson, 2004).

The view that federalism ensures limited government has been challenged by public choice arguments that it creates multiple independent sources of public authority, each of which has a tendency to continuous expansion, contributing to the growth of big government rather than its restriction. Competition between these multiple centres of political and bureaucratic power may contribute t the growth of Australian government, not just through the overlap and duplication of functions, but also through competition for political prestige and electoral support (Sansom & Alam, n.d.).

In terms of civil rights, the Australian government serves to protect rights and freedoms against a possible tyranny of the majority of government itself. The protection of human rights in Australia currently varies considerably between jurisdictions, with rights such as the freedom of assembly being now more secure in jurisdictions which have a charter of rights than those that do not (Crotty, 2009). In Conclusion, the Australian government is in a constant process of change, and the capacity of the conventions of democratic government to adapt has been an important advantage in this evolution. The challenge waiting ahead will be whether the country’s top leadership can find better ways of delivering sound and responsive control of Australian government in keeping with democratic traditions, as well as the expectations of the citizens.

Democratic Principles in Australians Government References

Birch, A. (2001). Concepts, theories of modern democracy (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Cook, I. (2004). Government and democracy in Australia. Victoria, Australia: Oxford

University Press.

Crotty, M. (2009). Turning points in Australian history. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Dahl, R. (2003). How democratic is the American Constitution? (2nd ed.). New Haven,

Conn.: Yale University Press.

Davis, F. (2015, March 9). Human rights in Australia will become a political plaything without consensus.

Retrieved March 18, 2015, from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/mar/10/human-rights-in-australia-will-become-a-political-plaything-without-consensus

Dalzell, S. (2015, March 12). New laws in Western Australia aimed at criminalising so-called “radical

protests” are undemocratic and a threat to basic civil liberties, lawyers say. New Protest Laws in WA ‘a Threat to Civil Liberties’ Retrieved March 18, 2015, from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-03-12/new-protest-laws-in-wa-a-threat-to-civil-liberties/6306126

Foley, C. (1996). Australian flag: Colonial relic or contemporary icon? Annandale,

NSW: Federation Press.

French, R. (2003). Reflections on the Australian Constitution. Annandale, NSW: Federation

Press.

Galligan, B. (1995). Federal republic: Australia’s constitutional system of government.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Galligan, B., & Roberts, W. (2001). Australians and globalisation: The experience of two

centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Galligan, B., & Roberts, W. (2004). Australian citizenship. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne

University Press.

Harris, B. (2002). A new constitution for Australia. London: Cavendish Pub.

Hart, P. (2008). Public leadership pespectives and practices. Acton, A.C.T.: ANU E Press.

Hudson, W. (2004). Restructuring Australia: Regionalism, republicanism and reform of the

nation-state. Annandale, N.S.W.: Federation Press.

Jones, T. (2008). The best Australian political writing 2008.

Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press.

Keating, M. (2004). Who rules?: How government control a privatised economy.

Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Kincaid, J. (2005). Constitutional origins, the structure, and change in federal countries. Montreal : Published for Forum of Federations and International Association of Centers

for Federal Studies by McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Lee, H., & Campbell, E. (2013). The Australian judiciary (2nd ed.).

Cambridge [U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Levey, G. (n.d.). Political theory and Australian multiculturalism. McGraw-Hill Education.

Lindell, G. (1994). Future directions for Australian constitutional law: Essays in honour of

Professor Leslie Zines. Sydney: Federation Press in association with the Centre for International and Public Law and the Law Faculty, Australian National University.

Manin, B. (2015). The principles of representative government. Corpus Books.

Patapan, H. (2000). Judging democracy: The new politics of the High Court of Australia.

Cambridge [England: Cambridge University Press.

Peabody, B. (2011). The politics of judicial independence: Courts, politics, and the public.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sansom, G., & Alam, M. (n.d.). Principles in local government legislation: Lessons from the

Commonwealth Pacific.

Smith, R. (2012). Contemporary politics in Australia: Theories, practices, and issues.

Port Melbourne, Vic.: Cambridge University Press.

Youtube. The government of Australia.

Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JBqyU2Hopg