Weight Management For Obese Children Order Instructions: For this paper I will be sending the details via email. It is important that they writer note that it is a continuation of order # 113827 and the writer must closely follow the sample paper attached in the email, The writer will also continue the paper from where it ends on the first paper completed in the order # above.

The writer will start from Step 2: Locate the Best Evidence and most importantly the writer will have to respect all the headings and sub-headings as in the sample paper. The sources for completing the paper cannot be more than 5 years old since it is an evidence base paper, and must include DOI where necessary. It is important to remember that they title of the paper we are working on is “Lack of proper education on patient with type 2 diabetes” The writer must also include at least 8 new sources formatted in APA , adding to the previous reference list of the first part of the paper.

I will email the sample paper containing the entire paper, the first part and the secoound part that has to be completed this week. I will also send the first part that was completed some weeks ago so that the writer can continue on that same paper since it is a continues paper. But again it is important that he note that it is a continues paper meaning he must add the reference to the previous ones and properly format them while respecting all headings and sub-headings just as in the sample paper.

Weight Management For Obese Children Sample Answer

Weight Management For Overweight/Obese Children: Parents Take Charge (PTC)

Quality care can be defined as appropriately identifying, evaluating, diagnosing and treating patients. The term quality in healthcare is correlated to professional knowledge and desired health outcomes (Institute of Medicine, 2012). It is also defined as being closely associated with patient safety (Mitchell, 2008). Clinical excellence is the goal of providing quality care. The process for achieving clinical excellence includes patient-centered care.

The patient is the focus and includes their concerns regarding their illness, values, beliefs and support network. Making the patient an active participant in their health care results in informed decision-making by the patient. Autonomy, nonmalfeasance, beneficence, justice and fidelity are ethical principles that are addressed as definitions of providing quality care and achieving excellence in primary care. America Nurses Association, American League of Nursing, and Center for Applied and Professional Ethics are organizations that set guidelines for excellence (Stanley, 2011). Quality and excellence in a clinical site is achieved through appropriate, comprehensive and timely care.

Examples of methods of providing clinical excellence include providing evidence-based treatment, the timely manner in which patients are seen from when they sign in, the offer of generics versus brand-name medications, patient education, open dialogue with patients and referrals to specialist as needed. Ethical considerations taken in account are the patient’s autonomy. The patient is provided information for full understanding of their illness, evaluation, treatment and alternative treatments so that the capability for informed decision-making is established.

Guidelines for the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children include how to assess whether people are overweight or obese; what should be done to help people lose weight; how to care for people who are at risk due to their weight and how to help people improve their diets and increase their physical activity (The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NHS, 2012). The intention of this paper is to present an evidence-based project (EBP) proposal for childhood obesity. Included in this paper is assessing the need for change in practice, appropriate theoretical models and frameworks, statement of problem, intervention, goals, systematic review of current research and design. Assessing the need for change in practice consists of identifying stakeholders, collecting internal data about current practice, comparing external data with internal data, identifying the problem and linking the problem with interventions and outcomes (Larrabee, 2012).

Step 1: Assessing the Need for Change in Practice

Stakeholders

The first step for the model of evidenced-base change is assessing the need for change in practice. To Abstract

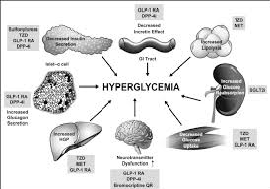

Diabetes is presently a popular chronic disease where the patient is required to make a wide array of self-management decisions daily as well as perform complicated care activities. Diabetes self-management education acts as the basis to assist the patients to navigate these activities and decisions. Kapoor and Kleinbart (2012) indicated that it greatly improves health outcomes. Diabetes education on self-management can be described as the process through which the skills, knowledge, and ability needed for the disease’s self-care is facilitated. As far as diabetes type 2 is concerned, patient education covers different aspects. Therefore, how effective the education is will greatly determine the extent to which the patient will engage in self-care. some of the aspects that patient education should cover includes the treatment options, disease process, causes, factors contributing to the disease, nutritional plan, exercise plan, knowledge about the medications that are prescribed, monitoring blood glucose, knowledge about the chronic and acute complications, individual approaches for promoting health, and the psychosocial issues (Mshunqane, Stewart & Rothberg, 2012). Regardless of how patient education is important, proper education still lacks, and there are a number of factors contributing to this. This paper aims at exploring the lack of proper education among diabetes type 2 patients.

Quality measures

Recently, NICE updated guidance on diabetes type 2 management. The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions developed the guidance. The then NICE guidelines are replaced and recommendations in some technology appraisals updated. The guidance will function as the only reference point for all care aspects. Worth noting, the guidance puts a lot of emphasis on patient education and complexities of management, lifestyle changes, as well as therapy side-effects have been made the priority. There is a recommendation that people suffering from diabetes type 2 should receive continuous education beginning from diagnosis, in addition to tailored dietary advice. The ADA’s (America Diabetes Association) position is that all diabetes patients should be provided with education and support from diagnosis and thereafter (Ruffin, 2016). The position statement is meant for the specific needs of people suffering from diabetes. This gives the indication that awareness among the patients is acknowledged as a very cardinal aspect for successful self-care.

Assessing the Need for Change in Practice

Stakeholders

The diabetes type 2 patients are the key stakeholders. These patients’ caregivers are also cardinal stakeholders since they mostly are concerned with caring for the patients. The entire healthcare team is a main stakeholder based on the fact that there are different aspects that should be monitored in patients on a regular basis (Green, 2014).

Barriers to Change

Some of the barriers that are likely to hinder change include the existing knowledge, fears and beliefs about the disease, accessibility to care, the influence of friends and peers, and health beliefs affect learning and consequently, the management behaviors. Therefore, it is worth pointing out that comprehending the expectations and needs of diabetes type 2 patients is cardinal in improving and initiating the education programs’ outcomes for effective self-care (Lee et al., 2013).

Facilitators to Change

Change can only be facilitated by making comprehensive explanations about the different aspects of the disease so that the patients can understand the impacts of failing to engage in the recommended practices. If patients have all the necessary details about the disease, then it would be easy for them to do away with the barriers that prevent proper information reception. For example, a patient who knows about the disease well is less likely to continue holding on health and spiritual beliefs that would only contribute to negative consequences (Garber, Gross & Slonim, 2010).

Internal Data

Many people present in healthcare institutions with the symptoms of diabetes type 2. An early diagnosis greatly ensures that complications are avoided and management done properly.

External Data

Everyone in Ontario ought to comprehend the disease’s seriousness since all are susceptible to it as well as the resulting health impacts. Diabetes type 2’s prevalence is alarmingly high. It is also expected to rise within the coming decade. In Ontario, more than 600,000 people suffer from the disease while many others are not yet aware that they have the disease. 4 out of 10 people suffering from the disease will develop long-term and debilitating complications. The disease is a known main cause of kidney disease, blindness, premature death, stroke, heart disease, and limb amputation among others.

Theoretical Model and Framework

The social learning theory that was crafted by Bandura is proper for exploring this issue at hand. It argues that people gain knowledge and skills after observing and imitating others, and through modeling. It also entails of aspects like memory, attention, and motivation. Learning occurs after people observe the attitudes as well as the behaviors of other people, in addition to the consequences of those attitudes and behaviors. Mostly, learning occurs through modeling and observation (Chijioke, Adamu & Makusidi, 2010). Therefore, if a given community continuously engages in activities aimed at managing and preventing diabetes type 2 which are encouraged by healthcare professionals, with lower disease rates, complications, and deaths as the effects, then all the communities around will imitate the particular community so as to realize similar impacts.

Problem

Regardless of the fact that various members in the community and from the healthcare team contribute in different ways to patient education, there is a great need for the providers as well as the practice settings to possess systematic referral processes and resources so that patients can receive education consistently. For example, the first education session might be offered by the healthcare professional while ongoing education sessions are offered by other practice personnel (Rosenstock & Owens, 2008). This can result to inconsistencies. Many times the programs that are designed fail to address the health beliefs, current knowledge, cultural needs, emotional concerns, physical limitations, financial status, family support, health literacy, medical history, and numeracy among other factors.

Problem Statement

There are numerous barriers that hinder effective patient education. Unless if those barriers are addressed, then even the most comprehensive education sessions will be useless (Stults-Kolehmainen & Sinha, 2014).

Possible Interventions

There is a great need for healthcare professionals to provide structured education to all diabetes type 2 patients and their care givers right from the diagnosis time. this should be accompanied by annual review and reinforcement. In addition, the practitioners ought to inform the caregivers and patients that the education is a cardinal component of diabetes care. The reviews should be conducted regularly based on need identification. Education should focus on all the good practice principles. In addition to this, the professionals should be keen at identifying the barriers that are likely to interfere with effective education reception or practice of all that was taught. The barriers should all be eliminated for effectiveness. Valencia and Florez (2014) noted that many patients anticipate diabetes education barriers. He, therefore, recommended that interventions at the multiple levels ought to address the socioeconomic and demographic diabetes education obstacles for effective self-management training (Zoepke & Green, 2012).

Critical Outcome Indicators

Definitely, following effective education among diabetes type 2 patients, numerous critical outcomes indicators would be evident. The patients would be able to make to make informed decisions about the treatment options that need, and understand more about the disease process. Moreover, they would be active in educating others about the causes and factors that contribute to the disease as a preventive measure. Moreover, following awareness creation on the proper diets, the patients would always be able to engage in appropriate nutritional and exercise plans, which would help prevent the related chronic diseases. The patients would also be able to engage actively and appropriately in monitoring blood glucose, taking right medications, taking the necessary measures to prevent the chronic and acute complications, promote health appropriately, and well as address the psychosocial issues (Augustyniak & Tadeusiewicz, 2009).

Goals and Purpose

Eliminating the barriers to diabetes education can ultimately improve patient experiences on education and care, improve populations and individuals’ health, as well as minimize diabetes- associated healthcare costs. In addition to eliminating the barriers, it is important to create an algorithm that defines what, how, and when the education should be offered to the patients.

Purpose Statement

Eliminating barriers to education and creating a proper algorithm can greatly promote effective education for better health.

References

Augustyniak, P., & Tadeusiewicz, R. (2009). Background 2.

Chijioke, A., Adamu, A. N., & Makusidi, A. M. (January 01, 2010). Mortality patterns among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Ilorin, Nigeria : original research. Journal of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes in South Africa, 15, 2, 79-82.

Garber, J. S., Gross, M., & Slonim, A. D. (2010). Avoiding common nursing errors. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Green, B. (June 06, 2014). Diabetes and diabetic foot ulcers : an often hidden problem : review. Sa Pharmacist’s Assistant, 14, 3, 23-26.

Kapoor, B., & Kleinbart, M. (April 01, 2012). Building an Integrated Patient Information System for a Healthcare Network. Journal of Cases on Information Technology (jcit), 14, 2, 27-41.

Lee YK, Ng CJ, Lee PY, Khoo EM, Abdullah KL, Low WY, Samad AA, Chen WS, & Lee, Yew Kong. (2013). What are the barriers faced by patients using insulin? A qualitative study of Malaysian health care professionals’ views. Dove Press.

Mshunqane, N., Stewart, A. V., & Rothberg, A. D. (January 01, 2012). Type 2 diabetes management : patient knowledge and health care team perceptions, South Africa : original research. African Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 4, 1, 1-7.

Rosenstock, J., & Owens, D. (January 01, 2008). Treatment of Type 2 Using Insulin: When to Introduce?.

Ruffin, T. R. (January 01, 2016). Health Information Technology and Change.

Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A., & Sinha, R. (January 01, 2014). The Effects of Stress on Physical Activity and Exercise. Sports Medicine, 44, 1, 81-121.

Valencia, W. M., & Florez, H. (January 01, 2014). Pharmacological treatment of diabetes in older people. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism, 16, 12, 1192-203.

Zoepke, A., & Green, B. (January 01, 2012). Diabetes and diabetic foot ulcers : an often hidden problem : general review. Wound Healing Southern Africa, 5, 1, 19-22.

facilitate this, identification of stakeholders is needed. The target population is children, age 10-13 years and their families. Final decisions to change behaviors lies with the children, but parents have great influences over the young child’s meals, snacks and physical activities. Participating parents therefore, will be the change agent, adding them to the list of stakeholders. Parents make informed decisions regarding the health of their children with the help of a primary healthcare provider (Burns, Dunn, Brady, Starr, & Blosser, 2013). Primary healthcare providers or nurse practitioners (NPs) are stakeholders that will assist in facilitating and implementing change.

Barriers to Change

Barriers for children’s outcomes include their maturity level; ability to understand or commit to the program and their parents, if they are reluctant to participate. The primary barrier to change is participation of the parents. Physical activity and dietary behaviors will need modification in and out of the home. Without the participation of the parents the goal for long lasting results will not occur. Barriers for the parents include health literacy level; language, if the primary language is not English and attitudes towards modifying foods and physical activity. Another barrier is the participant’s adherences to the nutritional guidelines provided because diet plans do not include the cultural foods that the family consumes.

Facilitators to Change

Facilitators to change include support from their primary care provider or NP that the participants know and trust, educational classes that will be designed to meet their family’s cultural and specific needs and physical activities that can be done as a family that includes utilizing the workout facilities and pool in the local gym.

Internal Data

Internal data (date retrieved within Porterville Valley PromptCare Medical Center) provides overweight/obesity information that is defined by height, weight, body mass index (BMI), frequency of physical activity and anthropometric measurements of children in rural Tulare County, California.

External Data

External data (data retrieved outside of Porterville Valley PromptCare Medical Center) include the following (Ogden, Carroll, Kit & Flegal, 2012; California Center for Research on Women & Families, 2011):

a). Approximately 31.8 percent of children and adolescents aged 2—19 years are obese in the United States

b). Approximately 1 in 3 (33.2 percent) of children and adolescents age 6 to 19 years are considered to be overweight or obese in the United States

c). An estimated 30.5% of children and adolescents aged 10-17 years are presently overweight or obese in California

d). The total percentage of overweight and obesity from 1999 to 2009 rose from 34.0% to 37.6% for 9-11 year olds in California

e). For teens ages 12-17 years in California, African American youth had the highest percentage of overweight/obesity (39.9%), followed by Latinos (29.4%), Asian/other (18.0%) and white youth (12.0%)

Internal data presents an estimated 30% of the children seen in Porterville Valley PromptCare Medical Center are overweight or obese. When comparing Internal data and External data a change in practice is needed to prevent the incidence of childhood obesity from continuing to grow at an alarming rate.

Theoretical Model and Framework

Since this EBP proposal involves changes in physical activity and dietary behaviors understanding the effects of behavioral and social aspect of the child is necessary. With this in mind, the Transtheoretical Model will be discussed as an integral element in the design of PTC, an overweight/obese child intervention proposal.

Transtheoretical Model (TM)

The TM integrates clinical psychology and concepts to support a framework to understand the behavior and motivate behavioral change. The concepts of TM are decisional balance, processes of change, self-efficacy and temptation. The five stages of the transtheoretical model are the following: precontemplation (not intending to change), contemplation (considering a change), planning or preparation (actively planning change), action (actively engaging in a new behavior) and maintenance (taking steps to sustain change and resist temptation to relapse) (Kadowki, 2012).

Decisional balance occurs in each stage and involves the weighing of advantages and disadvantages towards changing behavior. The processes of change are the steps that facilitate understanding and behavioral change. Self-efficacy is essential and will vary depending on the TM stage. Temptation to revert back to previous stages will exist throughout the model. Support from the individual’s social network will provide the encouragement to continue within the program’s parameters.

Problem

A correlation between obesity and chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and hypertension has been documented. Life expectancy for those who are obese is lower than those that maintain a normal Body Mass Index (BMI) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Earlier death rates in adulthood have been linked to excess weight in the younger ages (American Heart Association, 2013). The prevalence of obesity has increased three-fold over the past few decades and is reported as a public health problem within the United States (Singh & Kogan, 2010). The cost of health care for obesity-related diseases (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, etc) has skyrocketed and is predicted to continue to grow.

In the year 2000 an estimated $117 billion and $61 billion was spent both directly (medical costs) and indirectly (lost work time, disability, premature death and subsequent loss of income, etc) on overweight and obese individuals in the United States (Ward Smith, 2010). Chronic diseases linked to obesity were once seen mainly in adults, but are now becoming more and more prevalent in children. The National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), Division of Adolescent and School Health (2010) reported “the prevalence of obesity among children aged 6 to 11 years increased from 6.5% in 1980 to 19.6% in 2008…and among adolescents aged 12 to 19 years increased from 5.0% to 18.1%” (NCCDPHP, Division of Adolescent and School Health, 2010). Health concerns for obese children are a reality that must be addressed since the effects of early obesity will impact their health for the rest of their lives.

Problem Statement

The problem addressed in this EBP proposal is the growing rate of childhood obesity and the negative effects on the child, parents, family and community.

Possible Interventions

Intervention of childhood obesity includes early identification and participating in health promotion activities such as eating healthier and becoming more physically active, as early as possible, to reduce the likelihood of chronic diseases and increase the health in those at risk. Wojcicki and Heyman (2010) stated “studies have shown that early interventions can potentially prevent the development of obesity in school-age children, along with associated health conditions” (Wojcicki & Heyman, 2010, p. 1457). Interventions of childhood obesity include promoting a balanced diet and increased frequency of physical activity. But, with the complexity behind childhood obesity, it requires other interventions as well. Vos, Wit, Pikl, Kruff and Houdijk (2011) stated their family-based cognitive behavioral multidisciplinary lifestyle treatment “aims to establish long-term weight reduction and stabilization, reduction of obesity related health consequences and improvement of self-image by change of lifestyle and learning cognitive behavioral techniques” (Vos et al., 2011).

Education and physical activity should be provided to the whole family in order to ensure successful lifestyle change to occur for the child. It is hoped that by encouraging whole family participation that a lasting positive outcome would result. Pender, Murdaugh and Parsons (2011) stated “the significant role the family plays in the development of both health-promotion and health-damaging behaviors, beginning at a very early age is well documented” (p. 243). Golley, Magarey, Baur, Steinbeck and Daniels (2007) stated “parenting-skills training combined with promoting a health family lifestyle may be an effective approach to weigh management in prepurbertal children, particularly boys” (p. 517).

Critical Outcome Indicators

Outcome indicators aim to achieve results that matter to the patient (Larrabee, 2012). Critical outcome indicators include improved BMI, improved laboratory measurements, improved health behavior, improved dietary patterns and increased frequency of physical activity.

Goals and Purpose

The health goal is to improve outcomes of obese children living in rural Tulare County, California. Quality goals are to improve access to diagnostics, early treatment and continuity of care with the use of evidence-based practices that include family participation. Quality measures include the participant’s understanding of the nature of obesity, treatment, the negative impact of obesity on lifestyle and overall health. These aspects will be measured through documentation of BMI status, weight classification, percent of physical activity and nutritional counseling.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of the EBP proposal is to promote health and well being in overweight/obese children and their whole family through participation in a nine-week multi-component, family-based community intervention program.

The writer will start from this point this week as the fisrt part was completed some 4 weeks ago.

Step 2: Locate the Best Evidence

Diabetes, hypertension and other co-morbid conditions associated with obesity and morbid obesity that were once conditions identified in adults only, is now increasing in obese children. The prevalence of obesity has more than doubled in the past 25 years in children aged 6 to 11 and has more than tripled for adolescents aged 12 to 19 (American College of Preventive Medicine, 2011). Interventions have been implemented to target the child’s risk factors, the parenting styles and family characteristics and environmental factors. The focus of this review was on parental involvement given the fact that parents are directly influential in how and what the child eats, the level of importance of physical activity and the limitation of video gaming and viewing of television programs in the home. Parental modeling of healthy behaviors is also an essential element in shaping the child’s lifestyle habits and behavior.

A systematic review of research consisting of parental involvement as an element of the intervention design for overweight/obese children was conducted. Interventions included changes in diet, increases in physical activity and behavior modification. The intention was to establish an intervention that produced the greatest possible outcome for the weight management of overweight or obese children through parental involvement.

Methods

Search Strategy

The following databases were examined for this systematic review: Medline, CINAHL, ERIC, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PSYCLinfo, Science Citation Index, and Social Science Citation Index, from 2005 to present. Reference lists from recent studies were also viewed to reinforce what was found during the formal search. Searches for references from studies and reviews were an element of data sources and were conducted for the following: children (6-17 years); parent participation/involvement and obesity, nutrition or physical activity-related behaviors (overweight, snacking, exercise and screen time). Inclusion criteria were primary language (English); at risk factors or behaviors associated with obesity; healthy children as participants and inclusion of at least one of the following at the child’s level: nutrition or physical activity-related behavioral or anthropometrical outcome. The retrieved data included intervention and characteristics of the study (context, outcome measures and process factors).

Step 3: Critically Analyze the Evidence

Four out of the eleven studies were non-RCT with either no treatment control; three alternate delivery formats; no treatment and non-participant controls; and usual care control (Graf et al., 2006, Lane-Tillerson, Davis, Killion & Baker 2005, Korsten-Reck, Kromeyer-Hauschild, Wolfarth, Dickhuth, Berg, 2005, Schwartz et al., 2007). All non-RCT studies produced positive outcomes, but the strengths of their effectives were varied. The studies that focused on providing educational and motivational sessions to the parents resulted in the most positive outcomes. The studies that focused on the children separately did produce positive outcomes, but were found to not be as effective.

The remaining seven studies were RCT with either usual care control, assessor-blinding, alternate sun protection intervention or waitlist control (Nemet et al., 2005, Patrick, et al., 2006, Gillis, Brauner, Granot, 2007, Gollye, Magarey, Baur, Steinbeck, & Daniels, 2007, Kalavainen, Korppi, Nuutinen, 2007, McCallum et al., 2007, Savoye et al., 2007). All the RCT studies resulted in positive outcomes with strong effectiveness. Five of the studies had measures that presented high effectiveness with the parent and child attending sessions for diet modification, physical activity and behavior modification together. One study in which the parent and child (5-9 years) received interventions separately still presented positive outcomes although it did not measure as high an effectiveness as when the parent and child were together. Another study with the parent and child receiving interventions separately, produced positive outcomes and was seen to measure high effectiveness, but this was indicated as resulting due to the greater age (11-15 years) than those in the other studies.

Addressing nutrition, physical activity, video game/television screening time, behavioral skills and parental involvement for change are seen effective in decreasing childhood obesity. Interventions that had the agent for change as the child only, child and parent and parent only, resulted in positive outcomes (Kalavainen, Korppi, & Nuutinen, 2007; McCallum et al., 2007; Savoye, et al., 2007; Schwartz et al., 2007).

A lack of consistency among the approaches to the methods and design of the studies was evident which made identification of the best multi-component program for childhood obesity undecided. The studies that had the agent of child presented lower measures for effectiveness except for older children (11-15 years). This group presented greater measures for effectiveness due to the level of maturity and understanding. The way in which parents are involved in childhood obesity treatment interventions varied, but all focused on their role in helping the child lose weight. When the parent was the agent for change it was most likely to present with higher measures of effectiveness.

Parenting styles and level of parenting skills affect the consistencies of interventions for childhood obesity. The parent’s levels of commitment to the program were noted as being an issue for the importance attached to diet, physical activity and video game/television screen time. A higher measure of effectiveness was noted for parents that attended session with their child than those that attended separately.

The variation in parental involvement in the reviewed trials indicate that parental involvement was effective in improving childhood obesity, but was ineffective in providing evidence of how much parental participation was needed to increase the likelihood of successful weight management. The age of the child was a factor in relations to parental involvement. Parents and children attending more sessions together were found to present greater effectiveness when the child was 7-13 years. It was found that parents attending sessions alone were more effectives for older children (11-15 years) and younger children (3-7 years). Obtaining effective treatment with parental involvement is important to identify for future treatments for childhood obesity.

Other limitations of the studies reviewed include inconsistent sample sizes, homogenous samples and the wide diversity in weight, BMI and anthropometric measurements. The complexities of childhood obesity require research that addresses all elements that affect the child. A growing body of evidence advocates a multidisciplinary, family-focused approach to childhood obesity management, but there is a need to explore interventions that allow for parental factors, such as how much time is appropriate for change to occur, commitment for change and understanding the needs for change in order for optimal effectiveness of the intervention to take place.

Feasibility, Benefits and Risks of Implementing the Practice Change

The feasibility of implementing the practice change in a primary cares setting is increased because routine visits by participants allow for screening and management of overweight children. The NP is able to use the established relationship with the patient and their family to present the practice change. The cost of staff training for identification of overweight/obese children, delivery of intervention and evaluation of intervention proposal will be minimal due to the primary care facility being already prepared to do so. The staff is already able to and is equipped to do the following:

- Record height and weight

- Calculate the participant’s BMI

- Record waist circumference

- Record biceps and triceps skinfold measurements

Potential Barriers

Parents themselves are a potential barrier due to their cultural background and belief system, commitment to the program, socioeconomic status and the need for the parents to change shopping behaviors and own eating behaviors. Identified economic barriers are time and dollar costs. Other barriers include child preference, difficulty with modifying habits, difficulty with monitoring child behavior and need for assistance from family members. The access to physical activity programs, availability of other foods to fast food, modification of video games/television time, dietary information that is cultural appropriate, making the child’s behavior changes gradually are other identified barriers.

Benefits

The impact of childhood obesity on the child’s physical health, emotional health and social health has been documented and has resulted in research for the most successful interventions that includes parental involvement. Benefits of making the practice change include increased consistency of evidence-based childhood obesity screening, early identification and education. Present research documents evidence that diet modification, consistent physical activity, behavior modification and goal setting are elements for weight management (Burns, Dunn, Brady, Starr, & Blosser, 2013). It was found that counseling on the child’s BMI status was linked to parental perception of the child weight status, which resulted in the parents being almost 10 times more likely to be motivated to make healthy lifestyle changes (Haemer, et al., 2011). The practice change will utilize the increased parental perception from the education sessions to assist the child in developing healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Risks

The risk of health conditions and disease caused by being overweight or obese include breast cancer, coronary heart disease, type II diabetes, sleep apnea, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, colon cancer, hypertension and stroke. Obesity is the second greatest cause of preventable death in the United States (Get America Fit Foundation, 2010) and has resulted in $14 billion in direct medical costs (National League of Cities, 2010). For the overweight/obese child the risks involve cardiovascular disease, the development of diabetes, bone and joint problems, sleep apnea, social and psychological problems and several types of cancer (Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Risks involved for the healthcare facility in making the practice change include ineffectiveness, limited resources, time constraints, retention of participants and lack of evidence of best practice.

The effective interventions utilized counseling or education, handouts, motivation and support as behavioral strategies. But research on the amount and structure for parental involvement in weight management for overweight and obese children is limited and varied. Today’s overweight and obese children will most likely become tomorrow’s overweight and obese adults. The justification for making practice change to improve the clinical outcomes for childhood obesity through identified elements of parental involvement is essential for all stakeholders. Implications for design should include the cultural diversity and use of community resources.

References

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2011). Facts for families: Obesity in children

and teens. Retrieved from http://www.aacap.org/cs/root/fact_for_families/ obesity_in_children_and_teens

American College of Preventive Medicine. (2011). Adolescent obesity-Time for a

commitment to action: A resource from the American College of Preventive Medicine. Retrieved from www.acpm.org/resource/resmgr/…/ adolescentobesityclinicalref.pdf

American Heart Association. (2013). Overweight in children. Retrieved from

http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/Overweight-in

Children_UCM_304054_Article.jsp

Burns, C. E., Dunn, A. M., Brady, M. A., Starr, N. B., & Blosser, C. G. (2013).

Pediatric primary care. (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders.

California Healthline. (2013). Tulare County forum discusses obesity rates among

children in low-income families. Retrieved from http://www.californiahealthline.org/articles/2005/4/12/tulare-county-forum-discusses-obesity-rates-among-children-in-lowincome-families.aspx

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Childhood obesity facts: Health

effects of childhood obesity. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/ obesity/facts.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Healthy weight – it’s not a diet it’s

a lifestyle! About BMI for adults. Retrieved from

http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Steps to wellness: A guide to

implementing the 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans in the workplace. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nccdpgp/dnpao/hwi/downloads/Steps2Wellness_BROCH14 _508_Tag508.pdf#page=70

Gajda, R. & Jewiss, J. (2004). Thinking about how to evaluate your program? These

strategies will get you started. Retrieved from http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=9&n=8

Get America Fit Foundation. (2010). Obesity related statistics in America. Retrieved

from http://www.getamericafit.org/statistics-obesity-in-america.html

Gillis D, Brauner M, Granot E. A community-based behavior modification intervention

for childhood obesity. (2007). Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology, 20, 197–203.

Golan, M. & Weizman, A. Familial approach to the treatment of childhood obesity: Conceptual model.

(2001). Journal of Nutrition Education, 33(2), 102-107.

Gollye, R., Magarey, A., Baur, L., Steinbeck, K., & Daniels, L. (2007). Twelve-month

effectiveness of a parent-led, family-focused weight-management program for

prepubertal children: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 119(3), 517-

- doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1746

Graf, C., Koch, B., Bjarnason-Wehrens, B., Sreeram, N., Brockmeier, K., Tokarski, W.,

Dordel, S., Predel, H. G. (2006). Who benefits from intervention in, as opposed to screening of, overweight and obese children? Cardiology in the Young, 16, 474–480.

Haemer, M., Cluett, S., Hassink, S. G., Liu, L., Mangarelli, C., Petereson, T., Pomietto,

M., Young, K. L., & Weill, B. Building capacity for childhood obesity prevention and treatment in the medical community: Call to action. Pediatrics (128), 2, S71 -S77

Institute of Medicine. (2012). Crossing the quality chasm: The IOM health care quality

initiative. Retrieved from http://ww.iom.edu/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx

Kadowaki, L. (2012). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. Retrieved from

www.sfu.ca/uploads/…/GERO820_2012_Transtheortical_Mode.pdf

Kalavainen, M.P., Korppi, M.O., Nuutinen, O. M. (2007). Clinical efficacy of group-

based treatment for childhood obesity compared with routinely given individual counseling. International Journal of Obesity, 31,1500–1508.

Kaplan Higher Education. (n.d.). Fact sheet: The Kaplan University IRB at-a-glance.

Retrieved from http://www.kuctl.org/CTL_Develop/Courses_In_Progress/ PD523/doc_sharing/IRB_Fact_Sheet_6_25_2010.pdf

Korsten-Reck U., Kromeyer-Hauschild K., Wolfarth B, Dickhuth, H. H., Berg A. (2005).

Freiburg Intervention Trial for Obese Children (FITOC): results of a clinical observation study. International Journal of Obesity, 29, 356–361.

Lane-Tillerson C, Davis BL, Killion CM, Baker S. (2005). Evaluating nursing

outcomes: A mixed-methods approach. Journal of National Black Nurses Association, 16, 20–26.

Larrabee, J. H. (2012). Nurse to Nurse Evidence-Based Practice. ISBN: 0071493727

Publisher: McGraw-Hill

Mattessich, P. W. (2009). Evaluation of state nutrition, physical activity, and obesity

plans. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/EvaluationofStateNPAOPlans.pdf

McCallum, Z., Wake, M., Gerner, B., Baur, L. A., Gibbons, K., Gold, L., Gunn, J.,

Harris, C., Naughton, G., Riess, C., Sanci, L., Sheehan, J., Ukoumunne, O. C., Waters, E. (2007). Outcome data from the LEAP (Live, Eat and Play) trial: a randomized controlled trial of a primary care intervention for childhood overweight/mild obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 31, 630–636.

Mitchell, P. H. (2008). Chapter 1: Defining patient safety and quality care. Retrieved

from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2681/

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of

Adolescent and School Health. (2010). Healthy youth: Childhood

obesity. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/obesity/

National Institutes of Health. (2005). Research involving vulnerable populations PHS

398 application instructions for completing the human subjects section for proposed research involving children. Retrieved from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/hs/children4.htm

National League of Cities. (2010). Economic costs of obesity. Retrieved from

Nemet, D., Barkan, S., Epstein, Y., Friedland, O., Kowen, G., Eliakim, A. (2005).

Short- and long-term beneficial effects of a combined dietary-behavioral-physical activity intervention for the treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics, 115, e443–e449.

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K., & Flegal, D. M. (2012). Prevalence of obesity

and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. Retrieved from http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1104932

Patrick, K., Calfas, K. J., Norman, G. J., Zabinski, M. F., Sallis, J. F., Rupp, J., Covin, J.,

Cella, J. (2006). Randomized controlled trial of a primary care and home-based intervention for physical activity and nutrition behaviors: PACE for adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 160, 128–136.

Pearson, K. (2011). Starter knowledge for childhood obesity: Tackling childhood obesity as a new

clinician. Retrieved from http://nurse-practitioners-and-physician-assistants.advanceweb.com/Features/Articles/Starter-Knowledge-for-Childhood-Obesity.aspx

Pender, N., Murdaugh, C., & Parson, M. A. (2011). Health promotion in nursing

practice. (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Educational, Inc.

Rao, G. (2008). Childhood obesity: Highlights of AMA expert committee recommendations. Retrieved

from http://www.aafp.org/afp/2008/0701/p56.html

Regents of the University of California. (2007). Adolescent Psychosocial Scales: Health and

environment survey. Retrieved from http://famprevmed.ucsd.edu/pacedocs/HES.pdf

Savoye, M., Shaw, M., Dziura, J., Tamborlane, W. V., Rose, P., Guandalini, C.,

Goldberg-Gell, R., Burgert, T. S., Cali, A. M., Weiss, R., & Caprio, S. (2007). Effects of a weight management program on body composition and metabolic parameters in overweight children: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association, 297, 2697–2704.

Schwartz, R. P., Hamre, R., Dietz, W. H., Wasserman, R. C., Slora, E. J., Myers, E. F.,

Sullivan, S., Rockett, H., Thoma, K. A., Dumitru, G., Resnicow, K. A. (2007). Office-based motivational interviewing to prevent childhood obesity: A feasibility study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161, 495–501.

Singh, G. K. & Kogan, M. D. (2010). Childhood obesity in the United States, 1976-

2008: Trends and current racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities. Retrieved from www.hrsa.gov/healthit/images/mchb_obesity_pub.pdf

Stanley, J. M. (2011). Advanced practice nursing: Emphasizing common roles. (3rd

ed.). Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2012). Obesity, the

prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children. Retrieved from http://www.nice.org.uk/cg043

Vos, R. C., Wit, J. M., Pijl, H., Kruyff, C. C., & Houdijk, E. C. (2010). The effect of

family-based multidisciplinary cognitive behavioral treatment in children with

obesity: study protocol for a randomized controlled trail. Retrieved from http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/12/1/110

Ward-Smith, P. (2010). Obesity – America’s health crisis. Urologic Nursing, 30(4),

242-245. Retrieved from http://web.ebcohost.com.lib.kaplan.edu

Wojcicik, J., & Heyman, M. B. (2010). Let’s move-childhood obesity prevention from

pregnancy and infancy onward. New England Journal of Medicine, 362, 1457-1459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1001857

Appendix A

Golan and Weizman’s conceptual model: Familial approach to the treatment of childhood obesity, (Golan & Weizman, 2001).

Appendix B

Health & Environment Survey (Regents of the University of California, 2007).

Home & Environment Survey

Participant’s Name:________________________________________ Date:_________________________

Mother/ Father (Please Circle) Observation # ______________

Family Influences:

During a typical week, how often has a member of your household:

(Please check one number for each question only)

| Never | 1-2 days | 3-4 days | 5-6 days | Every day | |

| Watched your child participate in physical activity or play sports? | |||||

| Encouraged your child to do physical activities or play sports? | |||||

| Provided transportation so your child can do physical activity or play sports? | |||||

| Dona a physical activity or played sports with your child? | |||||

| Encouraged your child to eat fruits & vegetables? | |||||

| Discussed with your child how not eating fruits & vegetables can be unhealthy? | |||||

| Eaten fruits & vegetables with your child/ | |||||

| Encouraged your child to spend less time being sedentary (video/television screening time)? | |||||

| Discussed with your child how sedentary habits can be unhealthy? | |||||

| Helped your child to think of ways to reduce the time he or she spends on sedentary habits? | |||||

| Told your child that he or she is doing a good job reducing sedentary habits? | |||||

| Encouraged your child to eat lower fat foods? | |||||

| Eaten low fat foods with your child? | |||||

| Told your child that he or she is doing a good job eating low-fat foods? | |||||

| Encouraged your child to wear sunscreens? |

Food & Cooking

Are you the person who does most of the cooking in this child’s home?____Yes ____NO

If yes, please answer the following questions about cooking in your home.

If not, please answer the following questions to the best of your ability.

- When you prepare chicken, how often do you remove the skin?

- Never

- Occasionally

- Usually

- Always

- Never prepare chicken

- Which type of hamburger meat do you usually cook for your family?

- regular

- lean

- extra-lean

- never cook hamburger

- How often do you trim the fat off meat before you cook it?

- Never

- Occasionally

- Usually

- Always

- Never prepare meat

- What type of fat or oil do you use most often in cooking?

- lard

- meat fat (beef/pork/chicken drippings or chorizo)

- butter

- shortening

- margarine

- vegetable oil (olive, corn, canola, peanut oils, etc.)

g PAM or vegetable spray only

- never use fat or oil in cooking

- What type of mild o you usually serve?

- whole

- chocolate

- reduced fat (2%)

- low fat (1%)

- skim, nonfat, or powdered

- never use milk

- How often do you serve eggs?

- 5 or more times per week

- 3-4 times per week

- 1-2 times per week

- 1-3 times per month

- less than once per month

- never serve eggs

- When you buy or prepare refried beans, what type of fat are they usually made with?

- lard/butter

- bacon grease

- shortening

- vegetable oil

- PAM or vegetable spray

- none

- don’t know

- never serve refried beans

Neighborhood

About how long would it take to get from your home to the nearest businesses or facilities listed below if you walked to them? (Please check one box for each business or facility)

| 1-5 min | 6-10 min | 11-20 min | 21-30 min | 31+ min | |

| Convenience/small grocery store | |||||

| Supermarket | |||||

| Hardware Store | |||||

| Fruit/vegetable Market | |||||

| Clothing Store | |||||

| Post Office | |||||

| Library | |||||

| Elementary School | |||||

| Other School | |||||

| Your Job | |||||

| Bus Stop | |||||

| Park | |||||

| Recreation Center | |||||

| Gym or Fitness Facility |

Walking and Bicycling in your Neighborhood

Please check the answer that best applies to you and your neighborhood

| 1-5 min | 6-10 min | 11-20 min | 21-30 min | |

| Convenience/small grocery store | ||||

| Supermarket | ||||

| Hardware Store | ||||

| Fruit/vegetable Market | ||||

| Clothing Store | ||||

| Post Office | ||||

| Library | ||||

| Elementary School | ||||

| Other School | ||||

| Your Job | ||||

| Bus Stop | ||||

| Park | ||||

| Recreation Center | ||||

| Gym or Fitness Facility |

Neighborhood Surroundings

Please check the answer that best applies to you and your neighborhood

| Strongly Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Somewhat Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| The streets in my neighborhood are hilly making it difficult to walk or bicycle in. | ||||

| There are many canyons/hillsides in my neighborhood that limit the number of routes to walk or bike. | ||||

| There are sidewalks in my neighborhood that are well maintained (no cracks etc…) | ||||

| There are bicycle or pedestrian trails in or near my neighborhood that are easily accessible. | ||||

| Sidewalks are separated from the road/traffic in my neighborhood by parked cars. | ||||

| There is a grass/dirt strip that separates the streets from the sidewalks in my neighborhood | ||||

| It is safe to rid a bike in or near my neighborhood | ||||

| There are trees along the streets in my neighborhood. | ||||

| There is tree cover or shade along the sidewalks in my neighborhood. | ||||

| There are many interesting things to look at while waling in my neighborhood. | ||||

| My neighborhood is generally free from litter. | ||||

| There are many attractive natural sights in my neighborhood such as views or landscaping. | ||||

| There are attractive buildings/homes in my neighborhood. |

Home Environment

Please indicate/check, which items you, have in your home, yard, apartment, complex or community

| Yes | No | |

| stationary aerobic equipment (bicycle, treadmill, etc…) | ||

| dog | ||

| trampoline for jogging in place | ||

| running shoes | ||

| swimming poll | ||

| weightlifting equipment | ||

| toning devices (physioballs, ankle weights) | ||

| aerobic workout videotapes | ||

| step aerobics, slide aerobics | ||

| skates (roller, in-line or ice) | ||

| sports equipments (balls, racquets) | ||

| canoe, row boat, kayak | ||

| skis (snow or water) |

Household Rules

Please check the answer that best applies to you and your family.

| Never | Sometimes | Usually | Always | |

| Do you limit the number of hours your child is allowed to watch TV? | ||||

| Do you limit the number of hours your child is allowed to play video/computer games? | ||||

| Is your child allowed to play outside without wearing sunscreen? | ||||

| Do you limit the amount of sweet snacks your child is allowed to eat? | ||||

| Do you limit the amount of soda your child is allowed to drink? | ||||

| Do you keep candy, cookies, or chips around the house that your child can easily get? | ||||

| Is your child allowed to play outside the home after dark? | ||||

| Is your child allowed to play in the park without an adult watching? | ||||

| How often does dinner in your child’s home include vegetables? | ||||

| How often does breakfast in your child’s home include fruit and/or 100% fruit juice? | ||||

| Are adults allowed to smoke cigarettes in your child’s home? |

Home Computer & Internet Use

Please indicate which items you have in your home, yard, apartment, complex or community

| Yes | No | |

| Do you have a computer in your home? | ||

| Do you have access to the Internet in your home? | ||

| If not to question 2, do you plan to get Internet access in your home in the next 6 months? |

Healthy Lifestyle Strategies

Rate how often in the past month you (or a family member) has done the following things to help your child lead a healthy lifestyle. A healthy lifestyle is a way of life that includes participating in physical activity, eating nutritious foods, and taking precautions against skin damage from the sun (Please check one box for each question)

| Never | Almost Never | Some-times | Often | Very Often | |

| Helped your child look for new information on healthy lifestyles in places like magazines, books, or on the Internet? | |||||

| Talked with your child about the benefits he or she will get from making healthy lifestyle changes? | |||||

| Talked with your child about how one’s surroundings (home and neighborhood) can affect healthy lifestyles? | |||||

| Encouraged your child to say positive things to himself or herself about making healthy lifestyle changes? | |||||

| Encouraged your child to think more about the benefits and less about the barriers to being healthy? | |||||

| Helped your child keep track of his/her progress making healthy lifestyle changes? | |||||

| Helped your child set short and long-term goals to make healthy lifestyle changes? | |||||

| Rewarded your child for making and sticking to healthy lifestyle changes? | |||||

| Helped your child find ways to get around the barriers to making healthy lifestyle changes? | |||||

| Put reminders around the home to help make and stick to healthy lifestyle changes? | |||||

| Reminded your child to not to get upset if sometimes he/she can not stick to a healthy lifestyle change goal? | |||||

| Encouraged your child to try different ways to make healthy lifestyle changes so that he or she will have more options to choose from? | |||||

| Encouraged your child to do things to make being healthy more enjoyable? |

Physical Activity

In answering the following questions,

- Vigorous physical activities refer to activities that take hard physical effort and make you breathe much harder than normal.

- Moderate activities refer to activities that take moderate physical effort and make you breathe somewhat harder than normal.

During the last 7 days, on how many days did you do vigorous physical activities like heavy lifting, digging, aerobics, running or fast bicycling? Think about only those physical activities that you did for at least 10 minutes at a time

_________________ days per week How much time in total did you usually spend on one of those days doing vigorous physical activities?

____________hours ___________minutes

During the last 7 days, on how many days did you do moderate physical activities like carrying light loads, or bicycling at a regular pace? Do not include walking? Think about only those physical activities that you did for at least 10 minutes at a time.

_________________ days per week How much time in total did you usually spend on one of those days doing moderate physical activities?

____________hours ___________minutes

During the last 7 days, on how many days did you walk for at least 10 minutes at a time? This includes walking at work and at home, walking to travel from place to place, and any other walking that you did solely for recreation, sport, exercise or leisure

_________________ days per week How much time in total did you usually spend walking on one of those days?

____________hours ___________minutes

The last question is about the time you spent sitting on weekdays while at work, at home, while doing course work and during leisure time. This includes time spent sitting at a des, visiting friends, reading, traveling on a bus or sitting or lying down to watch television.

During the last 7 days, how much time in total did you usually spend sitting on a weekday?

___________hours _________minutes

Appendix C

Fruits & Vegetables Stages (Regents of the University of California, 2007).

Fruits & Vegetables Stages

Mark the answer that is true for you.

| 0 Servings | 1 Servings | 2 Servings | 3 Servings | 4 Servings | 5 Servings | |

| How many servings of fruits and vegetables do you usually eat each day (a serving is 1/2 cup of cooked vegetables, 1 cup of salad, a piece of fruit, 3/4 cup of 100% fruit juice)? |

If you answered 0 to 4, do you think you will start eating 5 or more servings of fruits & vegetables a day in the next 6 months

_________No, and I do not intend to in the next six months

_________Yes, I intend to in the next six months

If you answered “5” or “6 or more” servings, have you been eating 5 or more servings of fruits and vegetables a day for more than 6 months?

_________Less than 6 months

_________6 months or more

Fruits & Vegetables Change Strategies

The following are activities, thoughts, and feelings people use to help them change their fruit & vegetable intake. Think of any similar experiences you may be having or have had in the past month. Then rate How Often you do each of the following:

| Never | Almost Never | Sometimes | Often | Many Times | |

| I set goals to eat at least five servings of fruits & vegetables a day | |||||

| I have a friend or family member who encourages me to eat more fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I say positive things to myself about eating fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I think about the benefits I will get from eating fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I reward myself for eating at least five servings of fruits & vegetables a day | |||||

| I look for information about ways to eat more fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I look for information about ways to eat more fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I keep track of the number of fruits & vegetables I eat |

Fruits & Vegetables Pros and Cons

The following statements are different beliefs about eating fruits & vegetables. Please rate How Important each statement is to your decision to eat 5 fruits & vegetables a day. Use the following scale:

| Not Important | Slightly Important | Moderate Important | Very Important | Extremely Important | |

| I would feel embarrassed if other kids see me eating fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I would have more energy if I ate fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I would be doing something good for my body if I ate fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I would need too much help from my parents to eat fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I would feel healthier if I ate fruits & vegetables | |||||

| My parents would be pleased if I ate fruits & vegetables | |||||

| I would rather eat sweets or high fat snacks than fruits & vegetables |

Fruits & Vegetables Confidence

There are many things that can get in the way of eating fruits & vegetables. Rate How Sure you are that you can do the following in each situation. Please answer All questions.

| I’m sure I can’t | I probably can’t | Neutral | I probably can | I’m sure I can | |

| Eat 5 servings of fruits & vegetables everyday | |||||

| Ask someone in your family to buy your favorite fruit or vegetable? | |||||

| Ask for fruits & vegetables with your lunch? | |||||

| Drink 100% fruit juice instead of fruit punch or soda? | |||||

| Eat fruits or vegetables for a snack instead of chips or candy? | |||||

| As someone in your family to include fruits or vegetables with dinner? | |||||

| Eat fruits & vegetables when eating out at a restaurant? |

Fruits & Vegetables Family Support

During a typical week, how often has a member of your household (your father, mother, brother, sister, grandparent or other relatives):

| Never | 1-2 days | 3-4 days | 5-6 days | Everyday | |

| Encouraged you to eat fruits & vegetables? | |||||

| Told you that you are doing a doog job with eating fruits & vegetables? | |||||

| Eaten fruits & vegetables with you? |

Dietary Fat Stage of Change

Do you consistently avoid eating high fat foods?

_____NO and I do NOT intend to in the next six months

_____NO, but I intend to in the next six months

_____NO, but I intend to in the next 30 days.

_____Yes, and I have been, but for LESS than 6 months

_____Yes, and I have been for more than 6 month

Appendix D

Screening Time

Screening Time spent for Television, Computer and Video Gaming

Mark the answer that is true for you.

| 0 hours | 1 hour | 2 hours | 3 hours | 4+ hours | |

| How many hours do you spend watching television during your free time Monday-Friday? | |||||

| How many hours do you spend playing video games during your free time Monday-Friday? | |||||

| How many hours do you spend playing or doing homework Monday-Friday on the computer? | |||||

| How many hours do you spend “surfing” the Internet or playing online games during Monday-Friday? |

Appendix E

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

Diet History Questionnaire II

|

Today’s date:

| MONTH | DAY | YEAR | |

| Jan

Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec |

|___|___| | 2010

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

|

|

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 3 | 3 | ||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | |||

| 6 | |||

| 7 | |||

| 8 | |||

| 9 | |||

|

In what month were you born?

| Jan

Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec |

In what year were you born?

19 |___|___|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 5 |

| 6 | 6 |

| 7 | 7 |

| 8 | 8 |

| 9 | 9 |

Are you male or female?

Male

Female

- Over the past month, how often did you drink carrot juice?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

- Over the past month, how often did you drink tomato juice or other vegetable juice?

(Please do not include carrot juice.)

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

- Over the past month, how often did you drink orange juice or grapefruit juice?

NEVER (GO TO QUESTION 4)

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

|

3a. How often was the orange juice or grapefruit juice you drank calcium-fortified?

Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time

About ½ of the time

About ¾ of the time

Almost always or always

- Over the past month, how often did you drink other 100% fruit juice or 100% fruit juice mixtures (such as apple, grape, pineapple, or others)?

NEVER (GO TO QUESTION 5)

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

4a. How often were the other 100% fruit juice or 100% fruit juice mixtures you drank calcium-fortified?

Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time

About ½ of the time

About ¾ of the time

Almost always or always

- How often did you drink other fruit drinks (such as cranberry cocktail, Hi-C, lemonade, or Kool-Aid, diet or regular)?

NEVER (GO TO QUESTION 6)

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

5a. How often were your fruit drinks diet or sugar-free?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

- How often did you drink milk as a beverage (NOT in coffee, NOT in cereal)? (Please do not include chocolate milk and hot chocolate.)

NEVER (GO TO QUESTION 7)

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

6a. What kind of milk did you usually drink?

Whole milk 2% fat milk 1 % fat milk Skim, nonfat, or ½% fat milk Soy milk Rice milk Other |

Over the past month…

- How often did you drink chocolate milk (including hot chocolate)?

NEVER (GO TO QUESTION 8)

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

7a. How often was the chocolate milk reduced- fat or fat-free?

Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time

About ½ of the time

About ¾ of the time

Almost always or always

- How often did you drink meal replacement or high-protein beverages (such as Instant Breakfast, Ensure, Slimfast, Sustacal or others)?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

- How often did you drink soda or pop?

NEVER (GO TO QUESTION 10)

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

9a. How often were these sodas or pop diet or sugar-free?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

|

9b. How often were these sodas or pop caffeine-free?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

- How often did you drink sports drinks (such as Propel, PowerAde, or Gatorade)?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

- How often did you drink energy drinks (such as Red Bull or Jolt)?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

- How often did you drink beer?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

Over the past month…

- How often did you drink water (including tap, bottled, and carbonated water)?

NO (GO TO QUESTION 14)

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

13a. How often was the water you drank tap water?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

13b. How often was the water you drank bottled, sweetened water (with low or no-calorie sweetener, including carbonated water)?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

13c. How often was the water you drank bottled, unsweetened water (including carbonated water)?

Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time

About ½ of the time

About ¾ of the time

Almost always or always

- How often did you drink wine or wine coolers?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

- How often did you drink liquor or mixed drinks?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 1 time per day |

| 2–3 times in past month | 2–3 times per day |

| 1–2 times per week | 4–5 times per day |

| 3–4 times per week | 6 or more times per day |

| 5–6 times per week |

- How often did you eat oatmeal, grits, or other cooked cereal?

NEVER (GO TO QUESTION 17)

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

16a. How often was butter or margarine added to your oatmeal, grits or other cooked cereal?

Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time

About ½ of the time

About ¾ of the time

Almost always or always

- How often did you eat cold cereal?

NEVER (GO TO QUESTION 18)

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

17a. How often was the cold cereal you ate Total Raisin Bran, Total Cereal, or Product 19?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

17b. How often was the cold cereal you ate All Bran, Fiber One, 100% Bran, or All-Bran Bran Buds?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

|

Over the past month…

17c. How often was the cold cereal you ate some other bran or fiber cereal (such as Cheerios, Shredded Wheat, Raisin Bran, Bran Flakes, Grape-Nuts, Granola, Wheaties, or Healthy Choice)?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

17d. How often was the cold cereal you ate any other type of cold cereal (such as Corn Flakes, Rice Krispies, Frosted Flakes, Special K, Froot Loops, Cap’n Crunch, or others)?

| Almost never or never

About ¼ of the time About ½ of the time About ¾ of the time Almost always or always |

17e. Was milk added to your cold cereal?

NO (GO TO QUESTION 18)

YES

17f. What kind of milk was usually added?

| Whole milk |

| 2% fat milk |

| 1% fat milk |

| Skim, nonfat, or ½% fat milk |

| Soy milk |

| Rice milk |

| Other |

- How often did you eat applesauce?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat apples?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat pears (fresh, canned, or frozen)?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat bananas?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat dried fruit (such as prunes or raisins)? (Please do not include dried apricots.)

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat peaches, nectarines, or plums?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat grapes?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

Over the past month…

- How often did you eat cantaloupe?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat melon, other than cantaloupe (such as watermelon or honeydew)?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat strawberries?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat oranges, tangerines, or clementines?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat grapefruit?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat pineapple?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat other kinds of fruit?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat COOKED greens (such as spinach, turnip, collard, mustard, chard, or kale)?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat RAW greens (such as spinach, turnip, collard, mustard, chard, or kale)? (We will ask about lettuce later.)

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat coleslaw?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

- How often did you eat sauerkraut or cabbage (other than coleslaw)?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |

| 1 time per week | 1 time per day |

| 2 times per week | 2 or more times per day |

Over the past month…

- How often did you eat carrots (fresh, canned, or frozen)?

NEVER

| 1 time in past month | 3–4 times per week |

| 2–3 times in past month | 5–6 times per week |